New look, old flavors

Bumipura's new take on classic Malaysian-Singaporean flavors, and why food tourism and emerging cuisines go hand in hand

British historian E.H.Carr once remarked that history is an ongoing dialogue between the past and present, and the answers we gain from it change as contemporary preferences and values evolve.

That sort of dialogue is in the abstract, but it becomes a lot more tangible when it’s focused on food and our relationship with it.

Food, in some sense, is living history, the writing and rewriting of chapters in a cookbook that spans generations.

The part on rewriting gets me thinking a lot. How “revisionist” should someone get when reinterpreting a dish? What constitutes an authentic interpretation? Does authenticity, or faithfulness to an original dish, even matter at all?

Maybe it only matters if you claim to represent original flavors faithfully. Maybe it doesn’t. Maybe you just care about whether the food’s good.

But you don’t get to call a spade a spade just because it has a wooden handle and a metal head on one end.

This week, we look at:

Tastemakers: Bumipura’s bold creations in Mumbai

Hot Take: What Righteous Eats’ Brian Lee’s gets wrong about food tourism

Reimagining Malaysian, Singaporean classics: Chai Ming Yang’s Bumipura

How faithfully should we recreate dishes that no longer exist?

That’s the question that Mumbai-based Bumipura appears to answer. Founded in September 2024, this self-styled vestige of Malaysian-Singaporean culinary heritage, set in a future where Indian hegemony has swept over Southeast Asia, proudly states “inspired by the rich culinary heritage of Singapore and Malaysia” on its menu.

Sounds far-fetched? Not quite, once you’ve experienced its dark, mystical interior reminiscent of a Harkonnen setting in Dune.

Here, patrons discreetly sip away at mysterious elixirs, while waiters dressed in exotic Songket fabric uniforms take their orders. Photographs of prominent Malaysian and Singaporean landmarks imply a connection to distant realms outside of the bar’s confines – and a sense of homecoming for Bumipura’s founder Chai Ming Yang.

Bumipura launched on September 19, 2024. In just four short months, it has already earned mentions from leading publications in India, including Conde Nast Traveller, The Lab Mag and The Hindu.

Taking my first sip of Fat In-Between, I immediately understand why. Nothing else comes this close to replicating the exact flavors of mutton satay in cocktail form. My second try, the Nasi Lemak-themed Dear Seri, left me astounded by how precisely it recreates the dish’s signature flavors.

For Chai, his foray into reinterpreting culinary experiences began much earlier. Here’s how a serendipitous decision completely changed his life, his journey running Bumipura so far, and his take on authentic storytelling.

Finding a new outlet of creativity

Chai’s first medium of expression was not behind a bar, but through the viewfinder of a camera.

“I picked up photography while studying for my bachelor’s degree in architecture, and I’ve been in love with it ever since then,” he recalled.

That passion eventually led him to not only pursue a year-long photography postgraduate course in London immediately after his undergraduate studies, but also open a photography studio in Hangzhou, China, where he worked for three years.

But the sudden onset of COVID-19 in 2020 threw a spanner in the works. As the pandemic loomed, he decided to leave China and commercial photography behind to pursue more meaningful personal projects back home.

Among these projects was a bartending stint at a bar owned by one of his friends, which became his introduction to professional bartending.

But he quickly grew restless. Making good cocktails wasn’t difficult – finding the motivation to make good cocktails consistently was.

“If you see a place online, you feel inspired to go [to the actual location] and snap a photo of it,” he adds. “Creating a drink is also like that, when an idea hits me before I sleep, it’s an itch that keeps bothering me if I don’t try it out.”

To scratch that itch, Chai parted ways with the bar two months later and opened Exposed JB – a Johor Bahru-based four-seater, reservations-only bar concept inspired by photography processes and techniques. Its unique visual and culinary storytelling won several media accolades, and cemented his reputation as a mixology maverick.

Getting to the top of its game was a huge win for Exposed JB. But discouraged by Johor Bahru’s saturated bar scene, Chai was already looking outwards for something bigger.

Betting on Mumbai

On February 14th, 2024, an update appeared on Exposed JB’s Instagram account: Exposed JB would be indefinitely closed, and Chai planned to redirect all his attention to a then-undisclosed overseas project.

Find himself in Mumbai, he was convinced Bumipura had immense potential in the city’s fledgling bar scene.

“I saw bars and restaurants that catered to upscale clientele consistently packed, and patrons were splurging on dishes even though prices were almost on par with Singapore,” he remarked. “There’s also lots of high-rise development here, and I felt that people were living it up and getting richer.”

Where higher-end spending is concerned, he’s right on the money – spending on premium alcohol, personal care, and international travel among Indian consumers have all fared better than then spending on mass-market products in 2024.

Consumption of premium alcohol, in particular, is also expected to grow at double-digit growth rates between 2022 to 2027, as far as IWSR market forecasts show.

These trends are obvious for Bumipura, which sees an average customer spend between US$22 and US$33 – on par with high-end establishments serving specialty cocktails and premium spirits in Mumbai.

New market, new obstacles

Naturally, tackling a new market isn’t without its challenges.

For one, local patrons demanded both food and drink, and had significantly different dietary preferences.

“We started with only regular cocktails and then added craft beers and vegan cocktail options from guest feedback,” Chai recalled. Bumipura’s menu, which began with popular Malaysian and Singaporean dishes like Hainanese chicken rice, was also complemented with additional dishes that “catered to a wider palate” to make the food and drink selection “better balanced,” he added.

But that led to another problem: Bumipura’s food and drink selection is unfamiliar to most locally trained chefs. While bar bites are overseen by an Asian restaurant veteran, the chef still finds it difficult to create something that he has not done before without Chai’s step-by-step guidance.

Additionally, group sizes tend to be a lot bigger. While patrons in Malaysia and Singapore tend to visit alone or come in small groups of two or three, Chai easily receives groups of six to even ten patrons in Mumbai.

“This meant that a bespoke menu with a few signature drinks wouldn’t offer sufficient variety, since a group that size can easily sample the entire menu in one sitting,” he observed.

Some cocktails, like the Bandung-inspired Perfect Pair, also had to be tweaked after customer satisfaction did not meet expectations. “I thought it would do well as Indians drink a lot of tea with milk, but most customers who’ve tried it have told me that they do not like dairy products in their drink,” Chai quipped.

There was also a limited selection of materials and designs during the renovation phase, which constrained how he could feasibly execute his vision for Bumipura.

But staffing – a perennial headache for any food and beverage operator – remains his most pressing challenge. Chai has made stabilizing staff hiring the company’s top priority in the short term, citing how one or two staff members typically fail to make it for their assigned shifts daily.

Despite these challenges, Bumipura currently sees 20% of its patrons coming back for more. Chai observes that this crowd is steadily growing. Some have already requested for more cocktail concepts. Collaborations with other bars based in Mumbai are also on the cards, and so is a potential expansion.

“I’m thinking maybe a different part in India … [my plan for now] is to visit Bangalore a few more times in the near future,” he added.

Recreating authenticity

Perhaps what makes Bumipura’s food and drinks so enticing, is that they’re extremely faithful to the original flavors, yet considerate of local sensibilities.

They play within the sandbox of what proper Nasi Lemak, chilli crab, mutton satay, and thunder tea rice should taste like, but pushes the boundaries of those flavors are derived, and in what shape and form those flavors can assume.

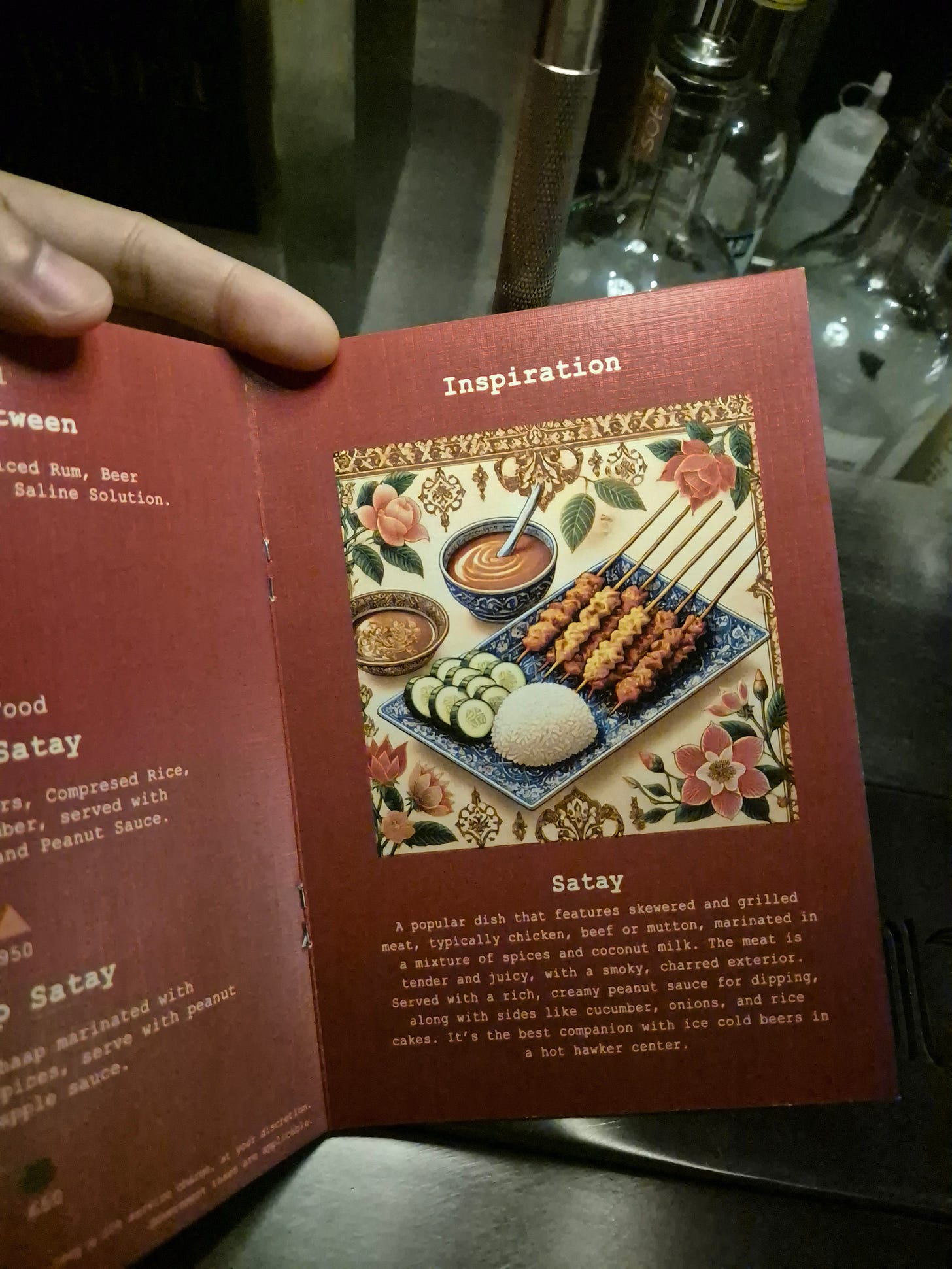

“I’m imagining that the real original recipe is gone, and nobody really knows how to make these dishes [one hundred years in an India-dominated future,” Chai said. “We’re in a future where we’re trying to showcase what we’ve read through books and stuff in a unique way, and that allows us to be more experimental.”

Before creating a dish, Chai spends significant time delving into every detail that goes into its preparation. He would first identify what ingredients were necessary to produce the right flavors and then incorporate these elements into a cocktail.

“We would then explain the inspiration behind each cocktail, and also why we chose a certain ingredient for our drinks,” Chai said. He added that this revelation often conveys a sense of adventure to guests, making them feel happy to have learnt and tried something new.

For this guest, Bumipura was definitely an adventure to remember. Chai and his team are reconstructing familiar flavors and taking them in bold directions, and I can’t wait to see what new concoctions they have in store.

No, food tourism isn’t being overtaken by “third culture” cuisines.

Righteous Eats gets a lot of things right about food, but co-founder Brian Lee’s guest essay for the NYT published December 31, 2024, leaves a lot to be desired.

In his essay, Lee makes three key points. Here’s my take on each of them.

Argument 1: Traditional food tourism is declining because of social media and cheap flights.

What Lee refers to by “traditional” food tourism isn’t made clear.

It’s ambiguous, and doesn’t consider how different parts of the world experience food tourism differently.

If that refers to the act of traveling specifically to consume certain foods, then the data doesn’t seem to agree. Hilton’s 2025 trend report, as well as the World Food Travel Association’s 2024 Report also indicate strong prospects for food tourism.

The claim that social media and cheap flights are causing a decline in “traditional” food tourism doesn’t hold water either.

The availability of food recommendations on social media casts a brighter spotlight on a wider variety of culinary experiences, while affordable plane tickets means more potential customers can savor not just the reel, but the real deal as well.

Argument 2: Good food from abroad is available at home, so there’s no need to visit their place of origin.

Aesthetically speaking, two versions of the same dish created in different countries from the same ingredients might look alike.

But they certainly won’t taste alike, since they’d be heavily curated to appeal to local palates or to overcome constraints on ingredient availability.

Writing off travel for the sake of good food because the same good food can now be found in one’s backyard also reduces food tourism to the act of consuming a food item. Often though, it’s about seeking experiences that accurately reflect local traditions and flavors.

Argument 3: The next big food trend is in emerging cuisines that fuse local and foreign flavors, not food abroad.

Lee’s final point warrants some merit. There is a definite uniqueness to emerging fusion cuisines that is worth paying attention to, and these cuisines may even mature to complement or supplant what we consider to be mainstream.

But it begs some questions: without tasting original flavors in their native settings, can our palates truly appreciate the new flavors of emerging cuisines? How do we know if a creation truly pays homage to an original, if we don’t know what the original is?

While Lee's point is valid, I believe a key factor in the success of fusion cuisines lies in their ability to resonate with the local palate.

That’s because while fusion cuisines emerge because of diaspora and immigration, a wider appreciation of these cuisines outside of migrant communities only comes when they resonate with the local taste palate.

How do you move the local palate closer to these new flavors? By motivating people to experience different flavors, and travel is one way to do so.

And as more people travel abroad to experience food in authentic settings, the higher the probability of new cuisines emerging. Purely from a numbers game perspective.

So, rather than two opposing forces competing for attention, emerging cuisines and food tourism actually go hand in hand.