Personality sells

Sandai Fishball's inextricable link to personal branding, and how F&B owners in Asia market themselves differently.

As a former journalist who’s currently building two businesses, I’m still struggling with putting myself in the spotlight.

It’s totally anathema for someone whose job was to give someone else a stage to stand on, to now take their turn on the stage. Sure, I’ve had several chances at public speaking, but even now it still feels … weird.

But then I remember my past conversations with startup founders. Most recently, I recall what Sandai Fishball’s Delonix shared with me: it’s not about selling, but telling a story and building trust.

Personality goes a long way in building a business, but I also ponder about the what-ifs when personality is taken too far. When the success of a business hinges on the reputation of a single person, it can be a rocketship - or a nosedive.

In this issue, we look at:

Tastemakers: Sandai Fishball’s Delonix Tan and his personal branding strategy

Better bite: How Asian F&B leaders think about personal brands

Making legacy fish balls cool again: Delonix’s Sandai Fishball

It’s 1.30 a.m. on a Sunday. At Kim Keat Palm Market, elderly men and women quietly prepare their stalls for the day ahead, the silence occasionally broken by the sound of shutters or shuffling feet.

Among them is 26-year-old Delonix Tan, a third-generation fish ball maker at Sandai Fishball, and his father. Like clockwork, the father-son duo carefully grinds fresh yellowtail fish into a fine paste – the key ingredient behind their signature fish balls. Brine is gradually added to the mix, and the duo begin to work their magic.

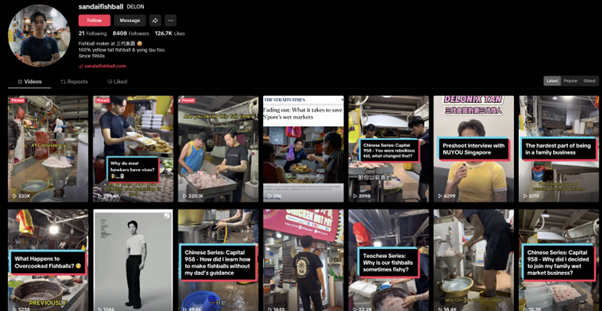

This reel is one of more than 140 TikToks that Delonix has posted on the stall’s official handle since 2021. From raw perspectives on running a family business to behind-the-scenes footage, his best-performing shorts have raked in nearly 320,000 views and landed him new opportunities to grow his business. Styling himself as a Gen Z artisan, his personal brand has also become a critical element of the business.

Here’s how Delonix reinvented Sandai Fishball, and the insights his journey offers for traditional market stalls looking to digitize. His playbook could offer some insights into supporting Singapore’s ailing wet markets.

Getting the ball rolling

The original Sandai Fishball concept was a hawker stall that briefly operated at Singapore’s Amoy Food Center in 2020. Delonix had secured the stall under the National Environment Agency’s Incubation Stall program, but COVID-19 measures forced him to permanently shutter it in August that year.

Delonix then pivoted his focus towards digitizing his father’s fish ball business. The stall already enjoyed a reputation for authentic, freshly made fish balls, and the main hurdle was scaling distribution.

“The play was to create more sales channels,” Delonix reflects. Going digital could allow the business to reach customers outside of nearby residents, especially since nearly 60% of Singaporeans discover new food products or restaurants through social media, according to a 2023 Rakuten Insight study.

To do that, Delonix adopted two strategies: repurpose Sandai Fishball’s social accounts to establish the fish ball stall’s digital presence and set up a pre-order service to cater to customers who do not patronize the stall during regular hours.

Keeping the Sandai brand was also a calculated move, as the name’s catchiness struck a chord with younger consumers.

“90% of our customer base is still largely customers from the immediate locale, but we’ve noticed that there is a growing number of new customers [who are part of a younger demographic]”, Delonix notes.

Since going digital, demand for Sandai Fishball’s products has become more consistent. “More and more of our patrons are returning customers, and a fair share of new customers also get to try our product,” notes Delonix. Sandai Fishball’s Instagram handle now has more than 20,000 followers, while its Facebook and TikTok accounts have over 10,000 and 8,000 followers respectively. Without spending a dime on marketing, the stalls’ pre-order slots, which now include most weekdays, are also filling up faster than ever.

A “mini celebrity” of the trade

Sandai Fishball isn’t the only wet market stall going digital, but what sets them apart from the competition is how central Delonix’s personal brand is to Sandai Fishball’s visibility.

For one, Delonix’s identity as a rebellious youth – turned - young wet market stall operator is undoubtedly unique. In a sunset industry largely overseen by older business owners, youth alone is a standout feature.

How he puts his identity across TikTok is more pivotal. On the platform, Delonix makes sure to keep interactions genuine. “The aim is to build trust and let it snowball over time,” he adds. There are no sales pitches in any of his TikToks. Instead, one finds deeply personal stories that emphasize relatability and transparency – key values that appeal to the Gen Z consumers.

Part of Delonix’s playbook is to also constantly deliver valuable content to his audience. In several videos, Delonix also positions himself as a fish ball making expert and community advocate. He offers practical tips such as handling overcooked fish balls and explains the economic constraints that fish ball sellers face today. He also opines on the latest developments affecting Singapore’s wet markets, and mulls over their future prospects.

A solid social media presence has opened many opportunities for Delonix to grow Sandai Fishball. In March 2025, Sandai Fishball bagged a two-month collaboration with Lau Wang Claypot which generated “record sales” for the latter. Delonix adds that Sandai also generated “significant revenue” from the initiative. A second collaboration with Singapore-based claypot chicken stall 8889 Claypot Chicken also generated “considerable revenue” for Sandai Fishball. Delonix declined to reveal exact figures.

A playbook for saving Singapore’s wet markets?

Delonix’s strategy of tying personal and business branding together has paid off for Sandai Fishball, but his approach is not without its share of challenges.

For one, convincing the older generation to buy in can be difficult. Digitization is often anathema to workflows that the older wet market stall owners – as well as hawkers – religiously abide by. The more technology disrupts their routines, the more difficult it is to convince them to embrace it.

Faced with his father’s initial opposition, Delonix initially drove Sandai Fishball’s digitization efforts solo. To film his TikToks, he initially made use of his smartphone and a simple camera stand tucked away in an obscure niche of the stall. He also single-handedly managed the pre-orders to minimize any additional burden on his parents. “Fundamentally nothing has changed … as long as my plans did not interfere with day-to-day operations, he was mostly nonchalant about them,” he adds.

Delonix’s experience is not unique. A 2024 study on key reasons that elderly hawkers gave for resisting digital payments included a lack of digital literacy, poor eyesight, and a fear of inconveniencing customers while they struggle with devices.

Another reason why resistance towards digitization in hawker centers and wet markets remains substantial is also because many of these stall owners cater to a regular clientele that is more inclined to pay in physical cash. But as Sandai Fishball shows, it’s viable to grow a customer base beyond the immediate locale by building an online presence.

A more significant challenge lies in manpower constraints. Demand for Sandai Fishball’s products has certainly grown since Delonix took the business online, but they have not been able to scale production volume high enough to take advantage of this growth.

“Nobody will come down [to the stall] at midnight to slog for you,” notes Delonix. Manpower shortages also translate to ingredient shortages, and while purchasing pre-processed fish meat can fill this gap, doing so will erode Sandai Fishball’s competitive advantage.

While challenges persist, Delonix believes that his approach can be reasonably emulated by his peers. Calling social media a low-hanging fruit for hawkers and wet market stall owners, he suggests that every business needs to be a media company, and anyone can be a mini-celebrity in their own trade.

“Keep it authentic, be genuine, and above all, have a good product,” he adds.

How F&B founders build personal brands across Asia

In a dinner conversation hosted by F&B marketing and commerce platform BentoBox several years ago, three American culinary heavyweights weighed in on the importance of chefs having a personal brand.

For New World cuisine pioneer Allen Susser, a chef had to have a story. “Without a point of view, you’re just cooking,” he reflected.

Thai-American chef Ngamprom “Hong” Thaimee’s goal was to ensure that people were “not eating Thai food but eating [her] food.” She suggested that authenticity isn’t about any specific cuisine but about who you are as a person.

Over in Asia, personal branding becomes much more nuanced.

This is a region that is perceived to revere humility and eschew self-promotion. A broad survey suggests that many Asian culinary leaders still speak through their craftsmanship rather than direct self-promotion. Yet, the success of several culinary mavericks fly in the face of stereotypes that paint building a personal brand as distasteful.

Take Japanese sushi chefs Jiro Ono and Hiroki Nakanoue, for example. Ono appeals to the traditional image of sushi chefs as shokunin, artisans dedicated to perfecting a single dish over a long period of time. Sushi Jiro mostly kept a low profile, with Ono focusing solely on craftsmanship and the quality of his products. On the other hand, Sushiyoshi’s Hiroki Nakanoue came into sushi as an outsider. He did not fit the typical shokunin mould, but came into his own with a striking visual identity that comprised dyed hair and a western-style chef’s outfit – a strong signal of his experimental approach towards sushi.

Spinning a personal brand in South Korea takes a louder, more media-savvy approach. Here, it is common for restaurateurs to take to mass and social media to humanize their business.

Perhaps nobody exemplifies this norm better than South Korea’s Paik Jong Won. Before his fall from grace, Paik grew his F&B empire on the back of his personal brand. Styling himself as a business-savvy, yet modest mentor, Paik came across as “an elite without elitism”. His ability to communicate recipes easily to a mass audience also won him public acclaim, so much so that when Paik’s company TheBorn Korea went public in November 2024, Hanwha Research Center hailed him as the “Korean version of Gordon Ramsay.”

Back home in Singapore, local celebrity chefs have taken diverse approaches to building their personal brand. Jereme Leung, who runs the show at Yi and formerly helmed the prominent Whampoa Club in Shanghai and Beijing, does not have a discernible digital persona. Both Local master chef Bjorn Shern and celebrated chocolatier Janice Wong, on the other hand, have a strong social media presence. Shern was formerly a judge on MasterChef Singapore and often appears as a host for food-related documentaries.

These various, albeit selective, experiences suggest that within Asia’s diversity of dining cultures, chefs in this part of the world navigate a dual imperative: to honor time-tested artisan traditions, while carefully introducing unique brand elements that emphasize themselves as participants in an ongoing narrative. Chefs that stand out all have a story to tell, but how they choose to tell that story still varies significantly in Asia.

📌 Smorgasbord is a one-stop section that lists offline/online events, readings, and resources for anyone building in F&B in Asia. This week’s events

Nothing noteworthy this week. Stay tuned for updates!

This week’s reads

As home-based cafes proliferate in Singapore, some F&B owners are calling out the trend for skirting regulations. The bigger issue: whether home-based businesses should be treated as commercial establishments.

Vietnamese tea franchise Phuc Long has launched its Phuc Long Hospitality, an in-house luxury hotel chain. The move is part of a trend of homegrown local brands moving beyond food and beverage retail into experiential travel.

Over in Seoul, Global fashion house Zara has also opened a new cafe in Myeongdong district. This follows a going trend of fashion leaders opening cafes in the South Korean capital, with Ralph Lauren and sneaker brand Golden Goose operating cafes in the city since September 2024 and July 2024 respectively.